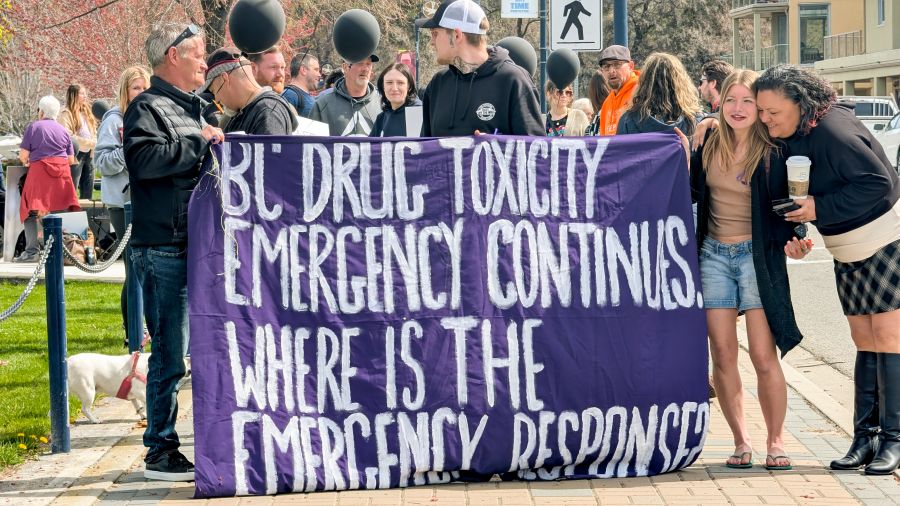

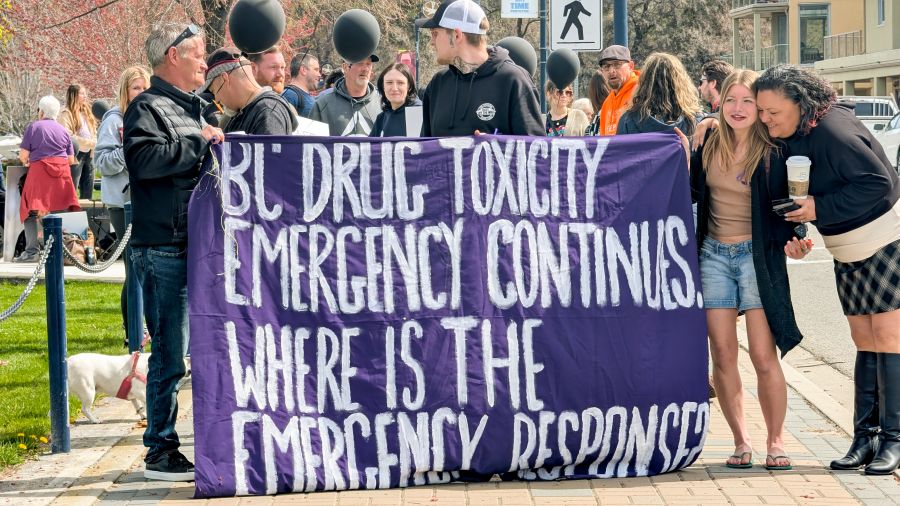

Black balloons mixed with tears and heartbreak – and a little hope too – Monday morning on the Penticton waterfront during the ninth annual commemoration of a 2016 provincial government declaration that BC was home to a public health emergency.

On April 14, 2016, then provincial health officer Dr. Perry Kendall, citing a dramatic increase in drug-related overdoses and deaths over the prior two years, officially declared the emergency.

According to a Province of BC news release from the day, it was the "first time the provincial health officer has served notice under the Public Health Act to exercise emergency powers."

The action was taken, continued the release, to "allow medical health officers throughout the province to collect more robust, real-time information on overdoses in order to identify immediately where risks are arising and take proactive action to warn and protect people who use drugs."

At the time, the declaration was hailed as forward-thinking.

The problem, say the several dozen people who gathered Monday at the Marina Way Park overdose memorial bench (itself debuted in 2023 by Penticton resident and celebrated drug survivor Gord Portman), is the lack of governmental action since.

"On April 14, 2016, the provincial government announced a public health emergency because the number of deaths related to the toxic drug supply was increasing," said event organizer Desirée Surowski as she walked with others along the Lakeshore Drive promenade.

When she's not putting together rallies, Surowski is the long-serving executive director of Penticton and Area Overdose Prevention Society (P+OPS). And Monday she was all about getting the word out.

"The hope was that by announcing the emergency, there'd be a mobilization of efforts to stop people from dying," she continued.

"Unfortunately, every year we’ve just seen increase after increase. People are still dying at the same rate they were nine years ago."

According to Surowski, the provincial government can effectively mobilize…when it wants to.

"We've seen when the government needs to arrive at a solution, as per COVID, they can," she said. "They can put the resources in place, they can get the resources to people.

"The only difference is who's dying."

Monday's rally began in ceremonial fashion at Portman's bench, where attendees shared stories and talked about answers then marched west along the promenade.

The event ended on the beach with roasted hot dogs.

"My hope is that we start treating this crisis as it's meant to be treated and we stop losing people," said Surowski.

We asked why, in her opinion, Penticton is typically so hard hit on a per capita basis by the overdose crisis. It's a trend you can see at the BC Emergency Health Services chart here, though you'll also see signs of hope in 2024.

"While Penticton has a lot of resources for a community," she said, "it doesn’t have the resources that are the most important. That being access to an overdose prevention site and a lack of available treatment opportunities in our valley for people who want to enter recovery services.

"We (POPS) used to run a public overdose prevention service, but the bus where we offered our mobile services broke down."

Surowski believes the impact of the crisis goes far deeper than Monday's group of rally goers.

"Whether people want to admit it or not, everyone is affected by the toxic drug crisis," she said.

"There are a lot of people who access the illicit market that are our neighbours and peers an coworkers. And the shame they feel prevents them from accessing services that could save their lives.

"So if you haven’t lost anyone yet and if nothing changes, you will. It’s inevitable."

As for Gord Portman, he let his personal experience speak for itself.

"I had 107 friends lost to addiction when I started that bench project in 2022," he told us.

"Now I'm at 137. We lost one on the weekend. We lost two the weekend before that. It just doesn’t stop."

To learn more about Penticton and Area Overdose Prevention Society, head here.